|

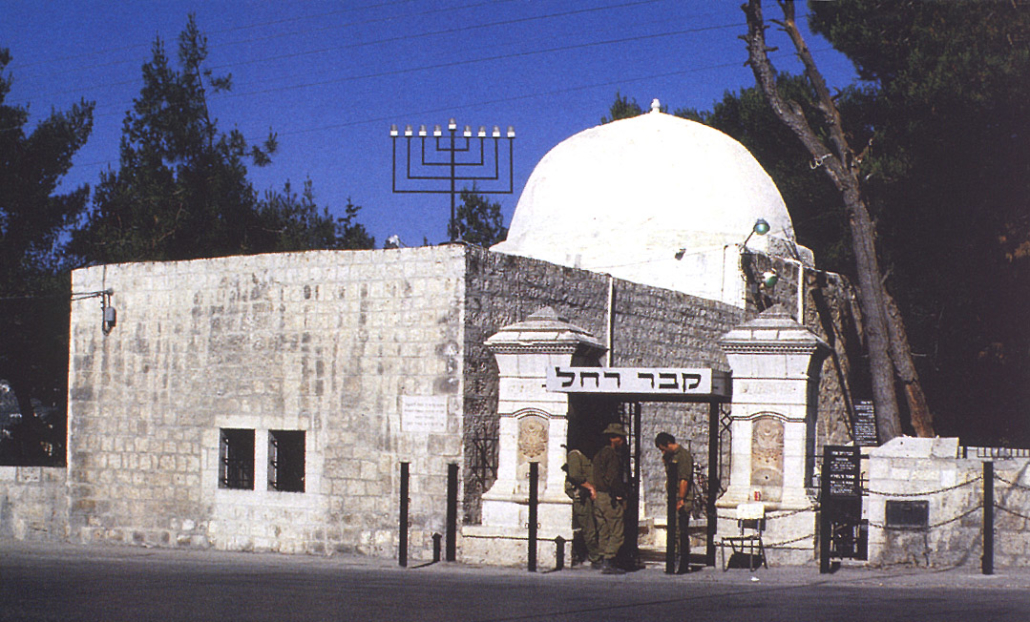

| Tomb of Rachel, northern outskirts of Bethlehem, courtesy, JewishIsraelTours.com |

[the

majority of this article is credited to Nadav Shragai, Senior Researcher at the

Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs]

Bethlehem today is a largely Muslim city with

a Christian minority, located about 5 miles south of Jerusalem. The Hebrew matriarch

Rachel died on the northern outskirts of Bethlehem while giving birth to

Benjamin. For centuries and to this day, her

grave has been a venerable holy site for Jews throughout the world. After

the conquest of Canaan by Joshua, Bethlehem was among the cities of Judah

allowing it to rapidly become a Jewish city. Its name means “house of bread”,

probably indicating that bread-making was an important industry at that time. It

was the scene of the story of Ruth who became the ancestor of David, and it was

through him, a native of Bethlehem, that the messiah would spring forth,

ushering in an era of peace and justice. In Christian tradition, that would be

Jesus Christ.

During the

days of Herod, and after, Bethlehem achieved historic importance as the

traditional birthplace of Jesus Christ, and as such, has been the site of pious

Christian pilgrimages throughout the centuries, even today. Since the

destruction of Jerusalem in 70, Bethlehem became less and less a Jewish city

and more and more a city of foreign peoples, mainly Christians. As early as the

second century, a stable in one of the

grottoes close by the town was pointed out as the spot where Jesus was

born. After the Arab conquest in the 7th century, a handful of Jews

still lived there. In the 12th century, the traveler Benjamin of Tudela

counted 12 Jews among the foreign population. His was also the first recorded

Jewish visit to the Tomb of Rachel. For decades afterward, the Tomb continued

to be an important site of Jewish pilgrimages. It was visited by Rabbi Ovadiah

di Bertinoro in the second half of the 15th century and by the 16th

century, the Arab historian Mujir al Din regarded Rachel’s Tomb as a Jewish

holy place. The building received its distinctive shape in 1622 when the

Turkish governor of Jerusalem, Mohammad Pasha, permitted the Jews to wall off

the site’s four pillars that supported the dome. Thus, for the first time, Rachel’s

Tomb became a closed building, which also simultaneously prevented Arab

shepherds from grazing their flocks at the site. Yet according to one report,

an English traveler claims this was done “to make access to it more difficult

for the Jews.”

Since the

18th century, the local Taamra tribe of Arabs would harass Jews visiting

the tomb and collect extortion money to enable them to visit the site. One of

the scribes who managed the accounts of the Sephardic Jewish kolel

(congregation) reported on the protection money that the Jews had to pay. According

to him, the payment was to the “non-Jews and lords of the lands who are called effendis…(15000)

Turkish grush…and these are the people who patrol the way of Jaffa Road, Kiyat Yearim,

the people of the Rama, the site of Samuel the Prophet, the people of Nablus Road,

the people of Efrat Road, the tomb of our Matriarch Rachel…so they would not

come to grave-robbing, heaven forbid. And sometimes they complain to us that we

have fallen behind on their routine payments and they come scrabbling on the

gravestones in the dead of night, and they did their things in stealth because

their home is there. Therefore, we are compelled against our will to propitiate

them.”

In 1796, Rabbi

Moshe Yerushalmi, an Ashkenazi Jew from central Europe who immigrated to

Israel, related that a non-Jew sits at Rachel’s Tomb and collects money from Jews

seeking to visit the site. Other sources attest to Jews who paid taxes, levies,

and presented gifts to the Arab residents of the region. Ludwig August Frankl

of Vienna, a poet and author, related that the Sephardic community in Jerusalem

was compelled to pay 5000 piastres to an Arab from Bethlehem at the start of

the nineteenth century for the right to visit Rachel’s Tomb. Taxes were also

collected from the Sephardim in Jerusalem to pay the authorities for various

“rights”, such as, among other things, payment to the Arabs of Bethlehem for

safeguarding Rachel’s Tomb. Rabbi David d’Beth Hillel, a resident of Vilna who visited

Syria and the land of Israel in 1824, testified that “…On the opposite hill, there

is a village whose residents are Arabs and they are most evil. A stranger who comes

to visit Rachel’s Tomb is robbed by them.” In 1827, Avraham Behar Avraham, an

official of the Sephardic kolelim in Jerusalem, obtained recognition from the Ottoman

Turkish authorities of the status and rights of Jews at the site. This was, in

practice, the original firman (royal decree) issued by the Ottoman authorities recognizing

Jewish rights at Rachel’s Tomb. The firman was necessary since the Arab Muslims

disputed ownership by the Jews of Rachel’s Tomb and even tried by brute force

to prevent Jewish visits to the site. From time to time Jews were robbed or

beaten by local Arab residents, and even the protection money that was paid did

not always prevail. Avraham approached the authorities in Constantinople on

this matter and in 1830, the Turks issued the firman that gave legal force to Rachel’s

Tomb being recognized as a Jewish holy site. The governor of Damascus sent a

written order to mufti of Jerusalem to fulfill the sultan’s order. A similar

firman was issued the following year. In 1841, Sir Moses Montefiore obtained a

permit from the Turks to build another room, with a dome, adjacent to Rachel’s Tomb

to keep the Arab Muslims away and to help protect the Jews at the site. A door

to the domed room was installed and keys were given to two Jewish caretakers,

one Sephardic and the other Ashkenazi. Jewish caretakers managed the site from that

time until it fell into Arab hands in 1948.

This

present status notwithstanding, Arab harassment continued. In 1856, James Finn,

the British Consul in Jerusalem, spoke about the payments that the Jews were

forced to make to Arab Muslim extortionists at some of the holy places

including Rachel’s Tomb: “100 lira a year to the Taamra Arabs for not wrecking Rachel’s

Tomb near Bethlehem.” In spite of all the dangers, Jews continued to make their

way to the site.

By 1905,

Bethlehem was a majority Christian city with a Jewish population of 1, a

doctor, according to the English traveler Elkan Adler (rising to 2 in 1922). Yehoshua

Burla, the father of author Yehuda Burla, was the caretaker of Rachel’s Tomb. The

last caretaker was Shlomo Freiman who often spoke of Arab harassment of Jews at

the site in the closing days of the British Mandate. He was prevented from

having any access once the site came under Arab occupation after the War of Independence.

After the Six Day War, Jewish pilgrimages began again. On October 19, 2010, the

anniversary of Rachel’s death, some 100,000 Jews visited the site.

Since Jews

are prohibited from living in Bethlehem, the nearest Jewish locations to the

city are the present neighborhoods of Gilo

and Har Homa in the southern part of

Jerusalem. Much of the land of the town of Irtas

was owned by a Jewish convert to Christianity in the mid-19th

century. But since then, the town has had no Jewish association.

No comments:

Post a Comment